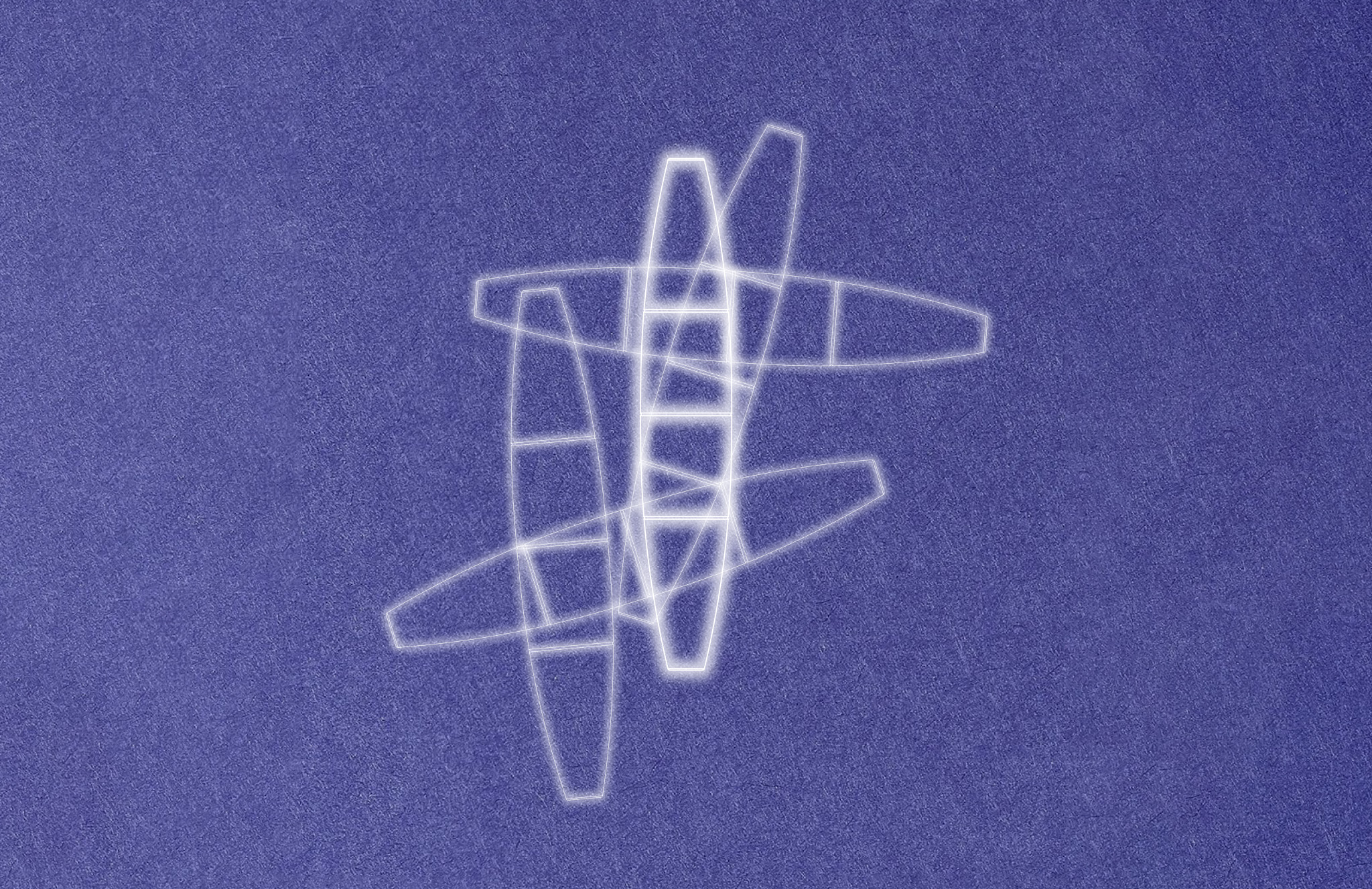

In the new series for the editorial project What’s in a Lamp?, British illustrator Jim Stoten reimagines Foscarini lamps in a series of hypnotic, infinite-zooming animations that feel like gateways—inviting viewers to explore universes within universes and pulling them into vibrant worlds of color, form, and imagination.

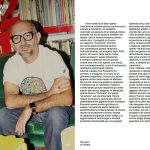

Living and working between Hastings, UK, and Venice, Italy, Jim Stoten channels his boundless imagination into illustrations, animations, and even music. His bold, kaleidoscopic style is instantly recognizable: playful yet intricate, intuitive yet deeply considered. He thrives on spontaneity, allowing ideas to flow organically to create artworks that invite viewers to visualize the vast and intriguing worlds within his mind. “I try not to overthink,” he says. “I want my work to feel intuitive, playful—like an endless discovery in progress.”

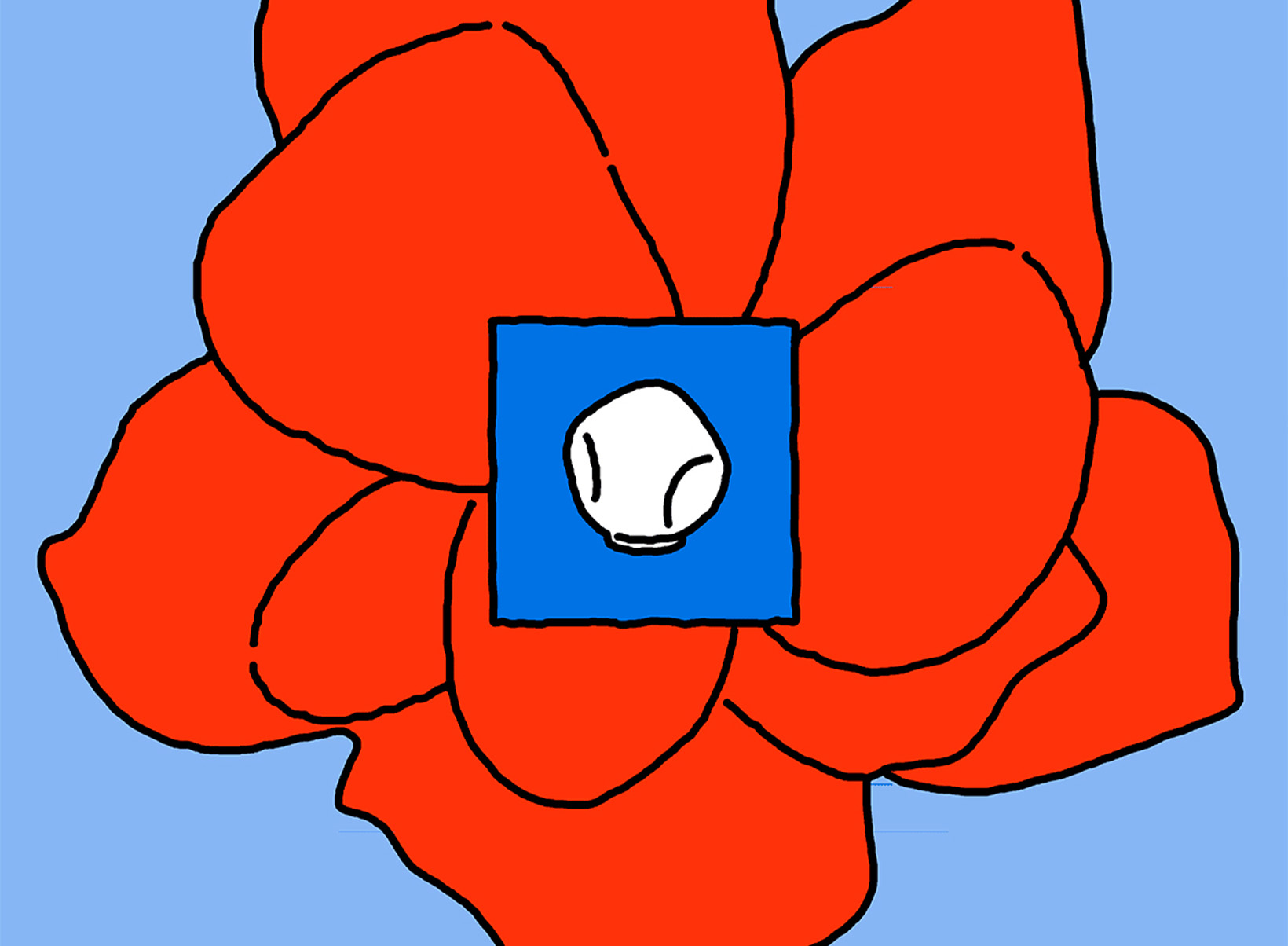

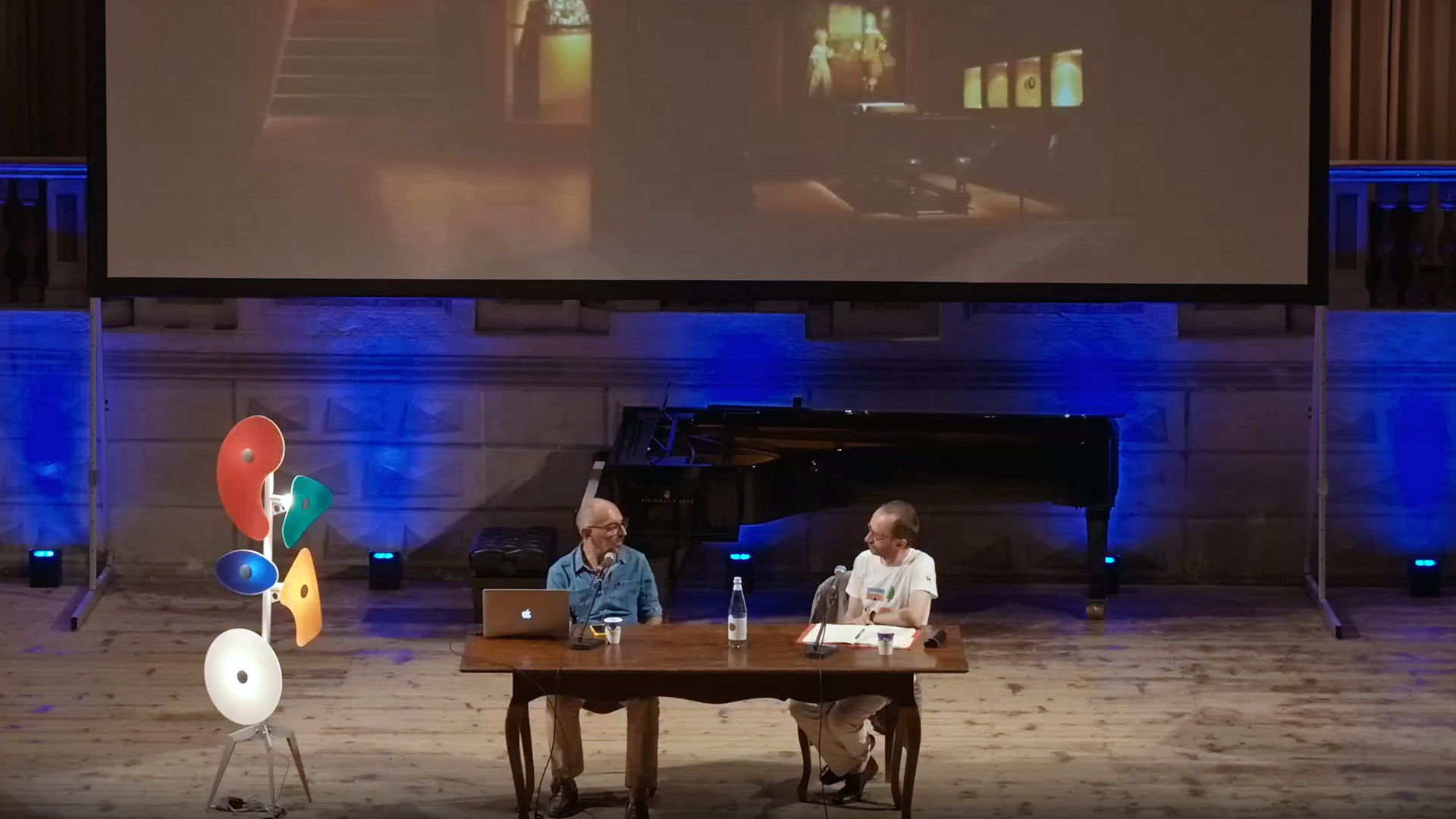

For Foscarini’s What’s in a Lamp? series, Stoten reimagined six of the brand’s iconic lamps, transforming them into infinite zoom animations that serve as portals to otherworldly dimensions. Each loop draws inspiration from the lamp’s unique aesthetic, design story, or the worlds sparked in Stoten’s imagination.

Hoba, with its organic, meteor-like shape, becomes a cosmic odyssey through the stars, leading to a surprising encounter with an astronaut. Chapeaux, with its interchangeable diffusers, opens a whimsical parade of hats, each with its own distinct personality. Nuée’s soft, cloud-like folds, evolve into a snowy landscape, where a skier gracefully glides through. And then there’s Lumiere, Kurage, and Orbital—each animation invites you deeper into Stoten’s vivid vision, urging you to lose yourself in the intricate details and layered narratives. It’s like a psychedelic deep dive into light and design.

“I wanted the animations to reflect both the aesthetic and the stories behind the designs while keeping things loose and playful, creating a world for each piece that felt cohesive yet full of surprises.”

JIM STOTEN

/ Artist

We had the opportunity to dive deeper into Jim Stoten’s unique perspective and artistic inspiration in this exclusive interview, which we’re sharing below. Experience how natural it feels to immerse yourself in Foscarini’s iconic designs through Jim’s vibrant, endlessly zooming journeys by exploring the entire What’s in a Lamp? series on our Instagram channel.

Tell us a bit about yourself and your journey as an artist. How did you get into illustration?

When I was a child I drew all the time as a form of entertainment for myself. When I applied and was accepted to study Illustration at the University of Brighton, all I knew about the course was that it encouraged all sorts of experimentation which I was really interested in. While studying I made lots of music, animations, drawings, prints and paintings and gradually after studying, I built up to where I am now.

How do the two sides of Jim Stoten—the illustrator and the musician—coexist and influence each other creatively?

I still really enjoy experimentation within creativity. Sometimes with both imagery and music, I feel I hit a wall – a place where I have worked so hard to get to, that I need a break. So then I turn to whichever way of working I haven’t done for a while, until I hit another wall and can turn back again. Basically, whenever I feel tired of drawing, I make music and when I’m tired of making music, I go back to drawing.

Your artistic aesthetic is incredibly unique. How would you personally describe your distinctive style?

I really have no idea. I know how other people describe it and I don’t always see what others see. I think my aesthetic is deeply rooted with how I think and what I am interested in conveying.

We’re curious about how your expressive style evolved over time. Did it develop naturally or was it the result of intentional research and experimentation?

It’s developed and changed over time. The work I’m doing now is very different to the work I was doing 10 years – in my opinion at least. It’s not intentional change, things just change as I find new things that attract my attention and hold my interest. Experimentation is exciting to me. I really like adding new things and taking away other things that I don’t feel are working anymore.

What’s your creative process like when working on your artworks? Do you have specific rituals or habits that you follow when you’re drawing?

Yes. If I’m in my studio, I make a pot of coffee and I have something on in the background, usually a film that I’ve seen before or an old TV chat show interview – something that I can listen to and occasionally stop to watch. If I’m not in my studio, maybe on a train or a plane or in a pub, I have music on my headphones and that’s it.

Your illustrations strike an intriguing balance between simplicity and complexity, where colorful minimal illustrations evolve into immersive video stories. How do you come up with your concepts?

The ideas behind the work are usually very immediate. I try not to think about that part too much. For me, overthinking ideas and approaches leads to uncertainty about the strength of an idea or concept. I like work to feel intuitive while I’m making it, which means that what is communicated varies depending on what I’m enjoying in making the work.

What inspired you to collaborate with Foscarini for this project?

I was excited by the freedom to move with this project. It felt like a nice opportunity to experiment and communicate simultaneously which is something that interests me greatly. It’s great to receive briefs like this where I am trusted to be free in terms of what I do.

Can you share the concept or inspiration behind the “What’s in a Lamp?” series?

For this project I allowed myself to mix my appreciation of the product’s aesthetic with my own loose interpretation of the background story behind the design. I wanted to be playful with both, in order to give myself the freedom to build an atmosphere that worked across all 6 animations.

Among the artworks in your “What’s in a Lamp?” series, do you have a personal favorite? If so, what makes it stand out for you?

I don’t have a favourite, I am happy with them as a set. The whole set is my favourite.

And, more in general, do you have a favorite subject to draw?

Horses.

Your work appears to offer a unique and original perspective on reality. How do you nurture this creative and alternative viewpoint?

I think my sketchbook is an important part of this process. I keep it with me at all times, and draw in it whenever I have time. I collect ideas in there that don’t have a place anywhere else for the time being, and mix it all up with the process of recording things I see, hear, remember, feel or just things I like. This means that any one page of my sketchbook is a big mix of everything that is happening inside of me and outside of me. My sketchbook always provides a good start point for how to approach projects.

What does creativity mean to you?

Creativity is a gift. It allows a person to process and digest any part of life that they wish to focus on, at the same time as bringing something that previously did not exist, into the light.

Discover more about the collaboration with Jim Stoten and the full series on the Instagram channel @foscarinilamps. Explore all the works from the “What’s in a Lamp?” project, where international artists are invited to interpret light and Foscarini’s lamps.