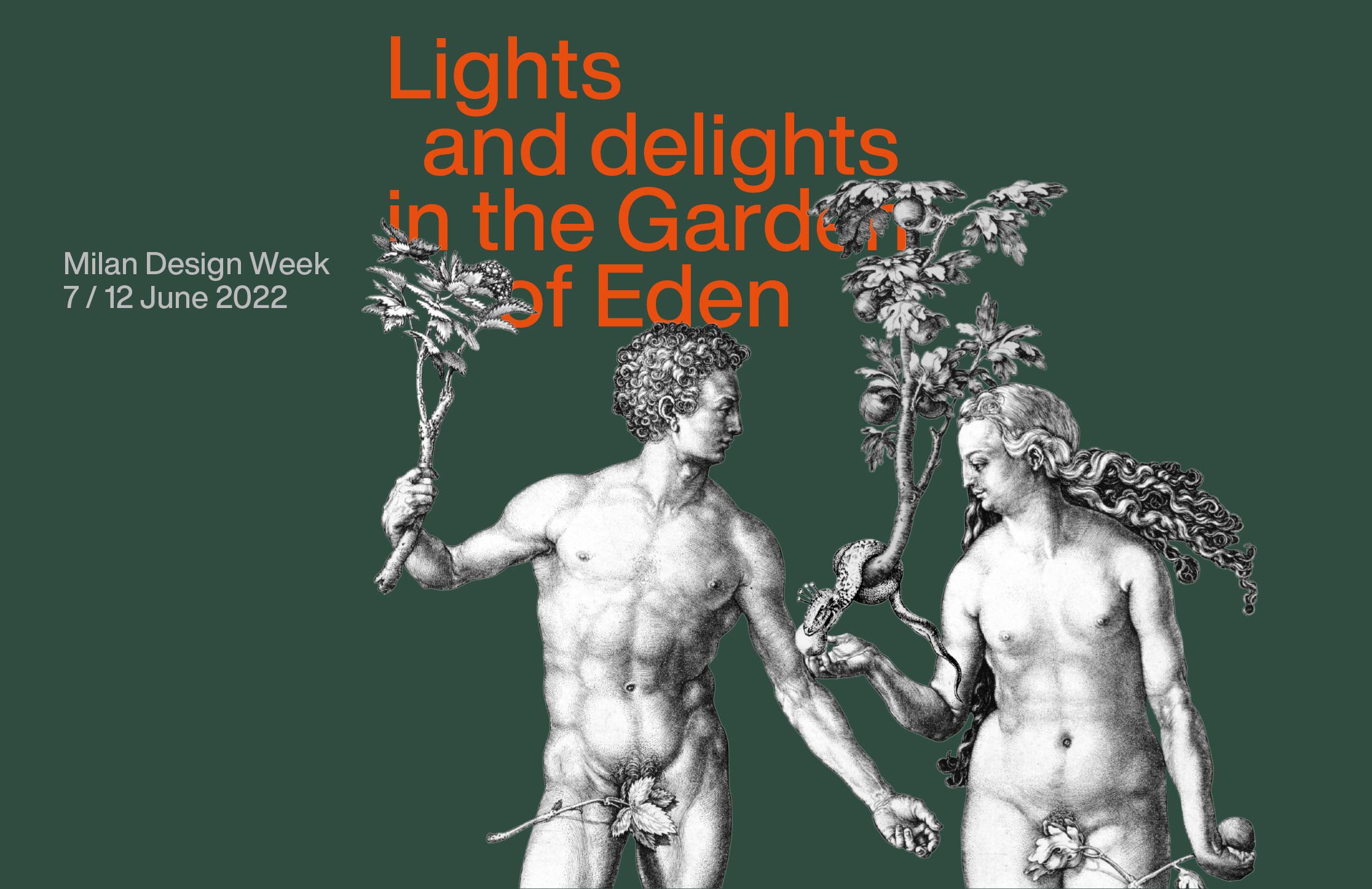

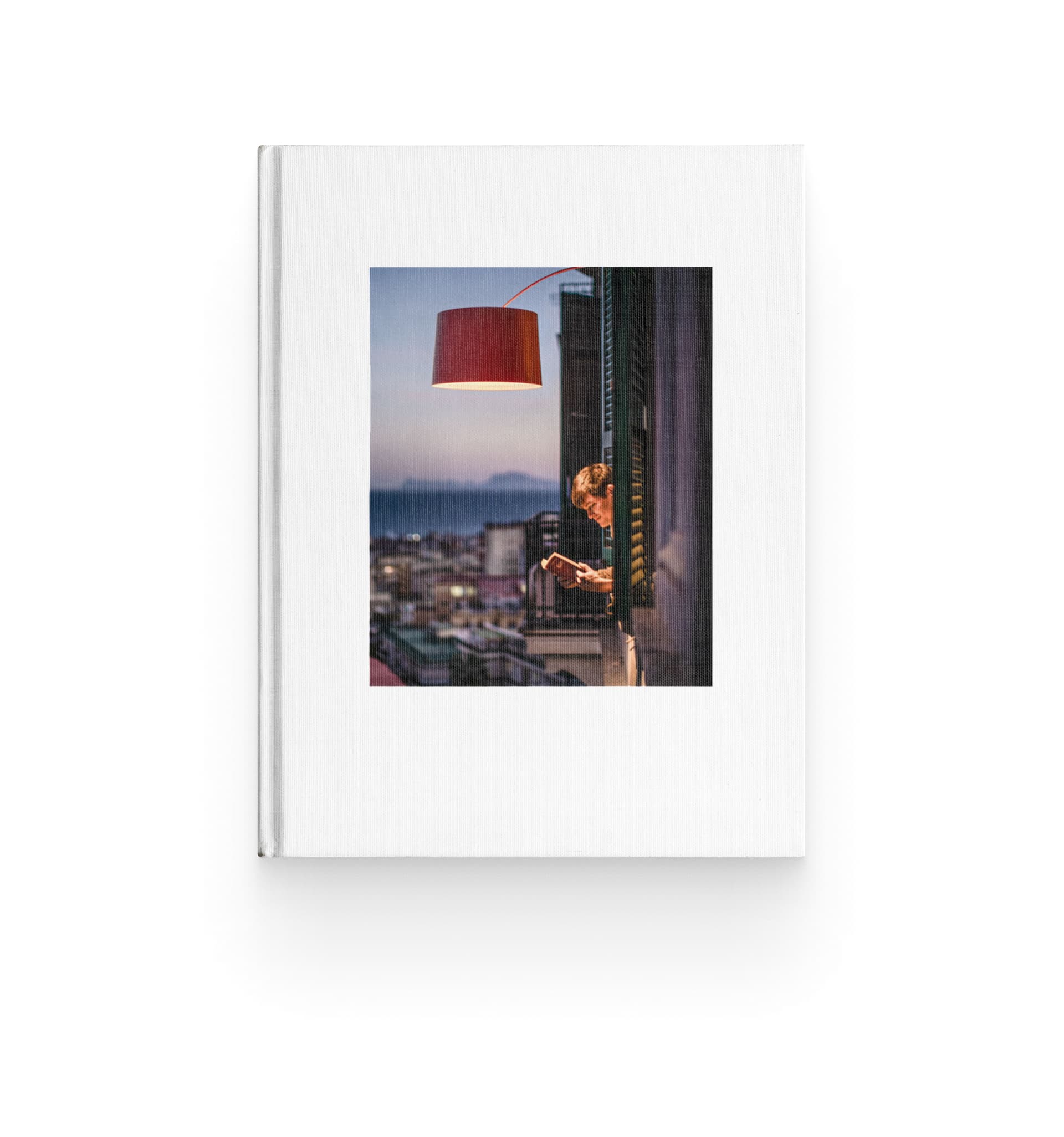

Francesca Lanzavecchia knows exactly what she wants: to design objects that never fail to make an impression. Not just a matter of aesthetics, but of that intense emotional resonance her projects attempt to set in motion.

For her, design is above all a way to resolve conflicts, a concept that covers various shadings. It means creating objects of affection, inventing solutions that foster a relationship of empathy between people and things, meaning that the things will be cared for and valued over time. It means respecting the diversity of bodies, inserting subtle visual dissonances that generate an emotional connection, to transform objects into metaphors, urging us to look beyond appearances. All these principles are expressed in Allumette and Tilia, the two chandeliers she has designed for Foscarini.

What do you think Foscarini was looking for, when they asked you to collaborate on this project?

“We approached Foscarini during the Salone del Mobile, starting a relationship of immediate, reciprocal interest. On their side, I think they wanted to understand how my approach – the constant pursuit of wonder and amazement in everyday life – could establish a dialogue with their language. On my side, I have always been fascinated by the company’s vision of design not as a mere industry, but as a factory of dreams capable of communicating humanity through projects, always enhanced by a subtly surreal tone. Within this complexity I found the opportunity to explore new ways of interpreting light, and of working on a project that was not just an end in itself. Not by chance, already at our first briefing the dualism between lightness and presence, order and disorder, emerged as a key theme.”

Is it rare for a designer today to find this sort of vision?

“At the level of storytelling, this vision seems to be shared by many, but it is rare to find a company that applies it in an authentic and systematic way from the inside – not simply as a communication strategy, but as a basic principle of the project, from the outset. Today there is a strong need for lightness and new narratives, but without a genuine and structured approach, like that of Foscarini, these tendencies cannot be transformed into concrete projects that reach the market. More often, what we see are products guided by the needs of marketing, on which to overlay narratives of an exploration that has never really happened.”

Let’s compare the two chandeliers…

“They share in the fact of not being single products. Both are important presences at the centre of a space, but they inhabit that setting with lightness, finding a subtle balance between technology, expression and poetry. In the end, both Allumette and Tilia have been envisioned to make light in an evocative way, transforming any space into a more intimate, lively and vibrant place.”

From the viewpoint of the project’s starting point, however, they are two very different systems.

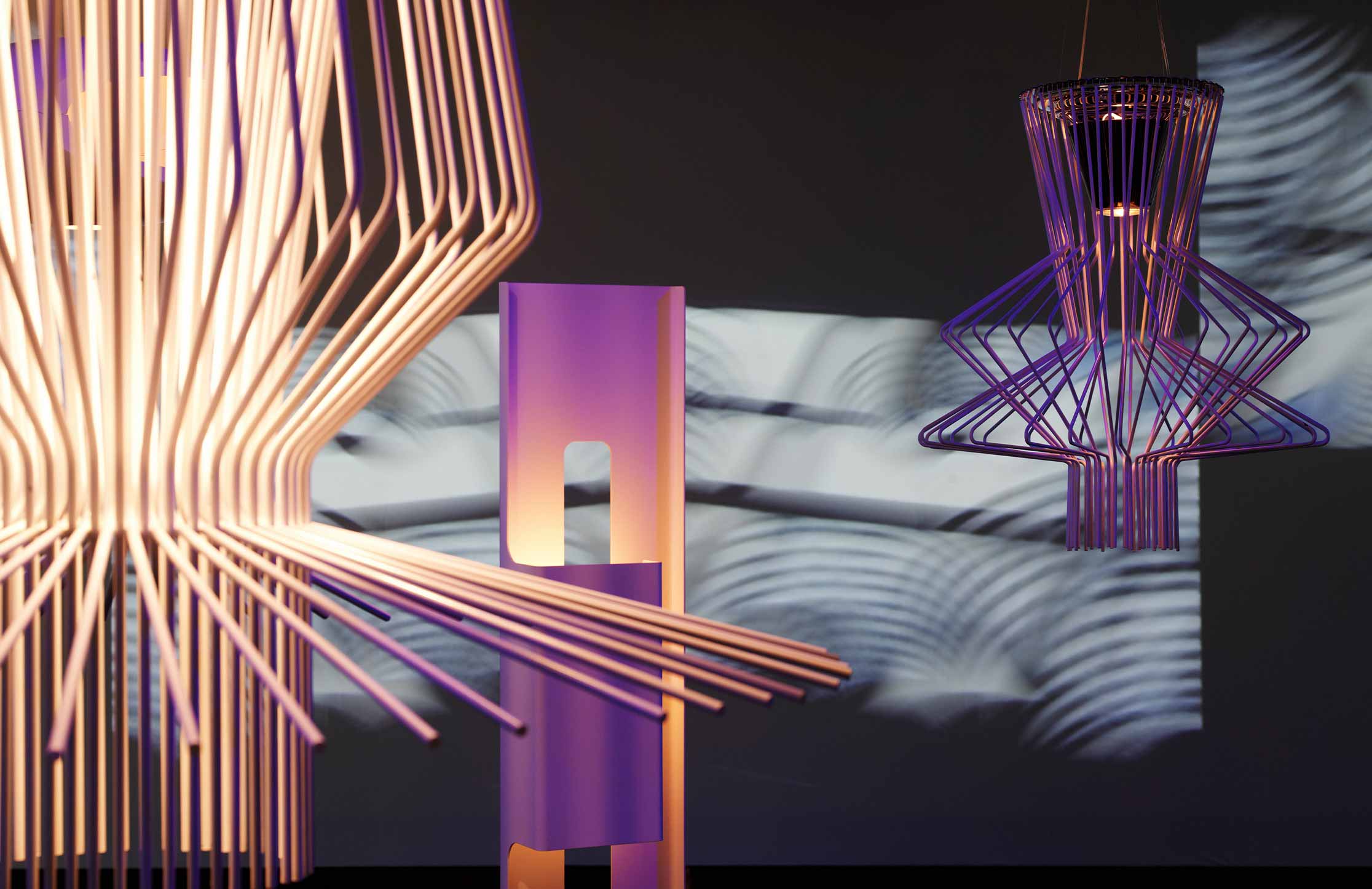

“Allumette is built on the balancing of opposites – full and empty, presence and transparency: I designed it by following an ‘engineering’ approach that focuses on structure, geometric tension, asymmetry. Tilia, on the other hand, is inspired by the spontaneous growth and fluidity of natural forms, and it is a sculptural representation of the invisible rules that enable natural structures to grow in space: the deltas of rivers, the veins of leaves, coral formations.”

Why have you moved in such different directions?

“I always investigate multiple paths. I like to get science, technology and physics involved, without ceasing to create familiar, intuitive objects, almost visual and tactile epiphanies.

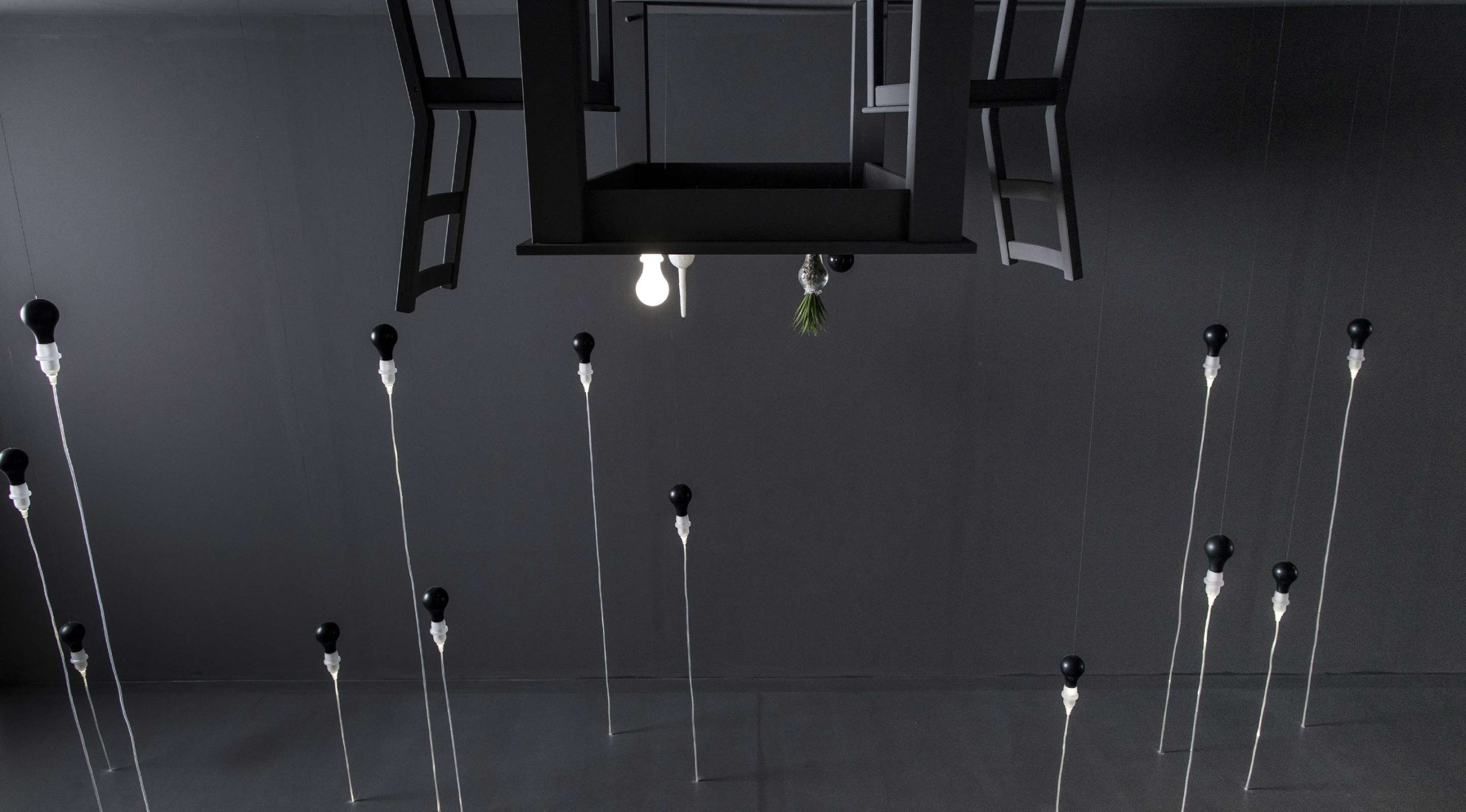

With Allumette, the starting point was the breakdown of a chandelier into its essential parts: I worked on technological elements, triangulation, irregular balances, trying to transform a complex object into a structure that would play with the contrast between tension and lightness.

With Tilia, on the other hand, I wanted to explore an idea of more organic growth, inspired by natural processes: branching, fractals, reticular structures. I tried to encode and transform them into a system of light that could expand in space, just as a tree stretches its branches towards the sun.”

We can observe them one at a time. What is the essence of Allumette?

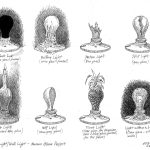

“It is a family of chandeliers rather than a single object; constellations at the centre of the room that balance opposites: lightness and presence, rigid geometry and soft lines. Allumette has been developed like a work of choreography, a presence that changes depending on the angle of observation. Its asymmetry is one of the most important keys of interpretation, along with the balancing of transparent and full zones, the rigidity of metal and the softness of the cable that references classic Venetian chandeliers. Then there is that magical moment when the light crosses and completely transfigures the lamp. The light source is composed of tubes of transparent methacrylate, attached to the arms. The LED light runs inside them and emerges from the extremities, scratched and conical, transforming ethereal elements into vibrant presences, like small flames suspended in space.

The result is a sense of discovery, an experience similar to Proust’s madeleine: an object that transmits intimate familiarity, while still being totally without precedent.”

Speaking of familiarity, at first glance Allumette seems to be indebted to the 2097 by Sarfatti. Although then the play of asymmetry steers us away from this archetype. Have you consciously developed this game of citations?

“Sarfatti’s chandelier has been emblematic, and a great inspiration in this project. Not so much in the forms, as in its ability to aptly express the role of technology, making it explicit for the first time: the exposed light bulbs, the presence of the wiring. I was also fascinated by the design’s way of conquering the space around a central fulcrum. From this point, however, for Allumette I followed a different inspiration, built on the idea of the original light sources, namely the candle, and the triangulation of the arms with variable length and geometry, making it possible to place the barycentre off axis.”

You said the moment of ignition is crucial. How did you design it?

“I wanted to create a cloud of light around the table. For this, symmetry was crucial: a symmetrical object would generate a sphere of light, while I wanted a luminous cloud, with warm, natural light. The basic idea was to exploit the magic of the reflection in a transparent tube, with the light that is pushed upward and then descends, reflected. The light spreads all around, without acting as a spot, without being directed only towards the ceiling. In the moment of ignition, each transparent part comes alive and the whole balance of the object changes.”

When do you realize that you have found the right solution for a project?

“I usually move forward with many projects at the same time. I arrive at a meeting with the client with five ideas, then I discard some of them prior to the presentation, to choose the one that convinces me most. I rely a lot on 3D to quickly test ideas and historical research: for Allumette, I studied the first chandeliers like candleholders, and broke down every part to reconstruct it in a contemporary way. It is a process of lateral thinking: combining technical know-how and personal sensations to grant form to something new.”

What was Foscarini’s role in the project development?

“This project was a wonderful dance. The most exciting moments are at the start, when you know nothing, and when the collaborative work begins. There were technical challenges – which I, as a neophyte in the field of lighting, was unaware of – with an impact on form, with which we had to come to grips. Foscarini worked on these aspects with extreme care, balancing engineering and design vision.”

Now let’s talk about Tilia

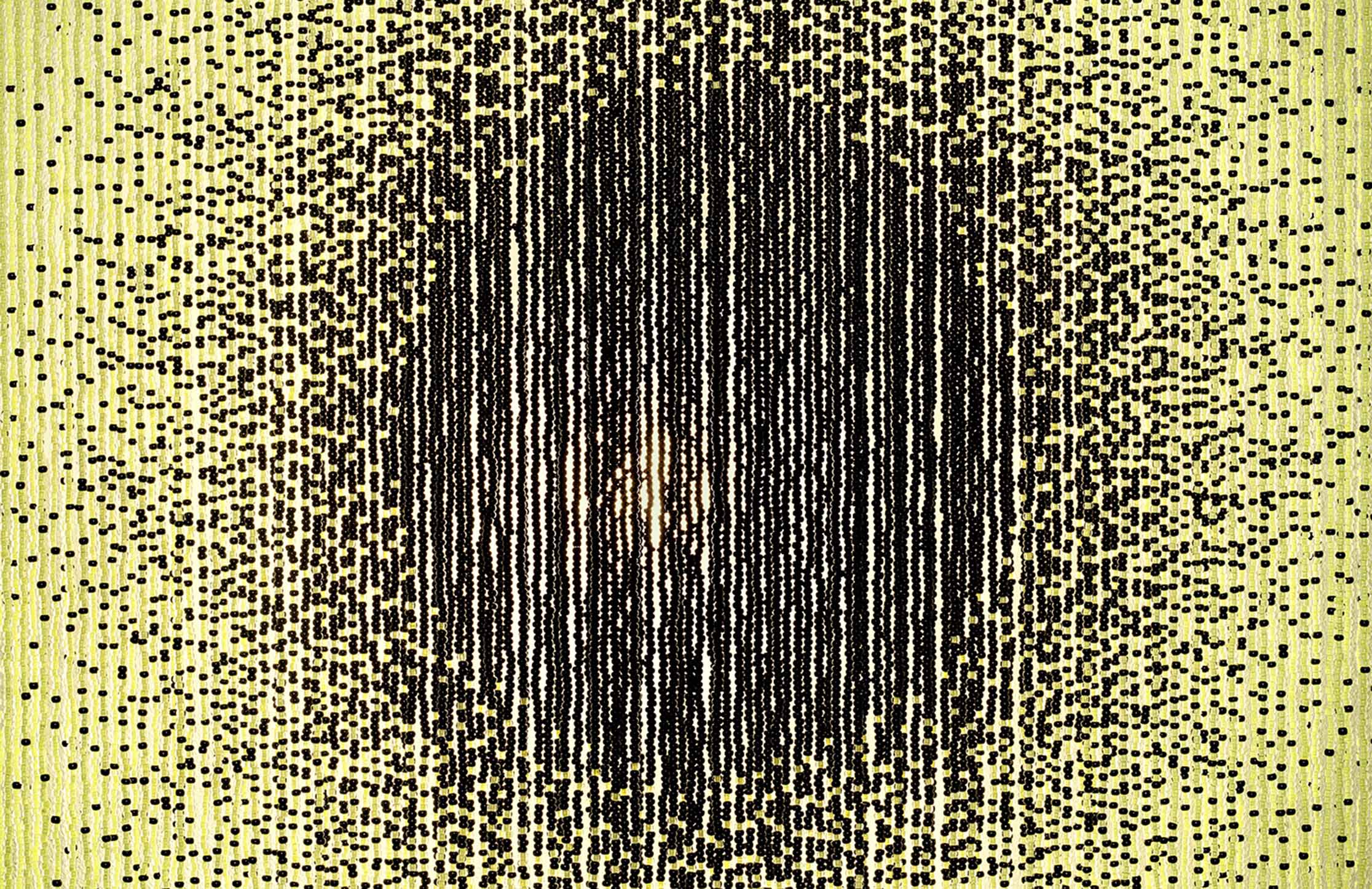

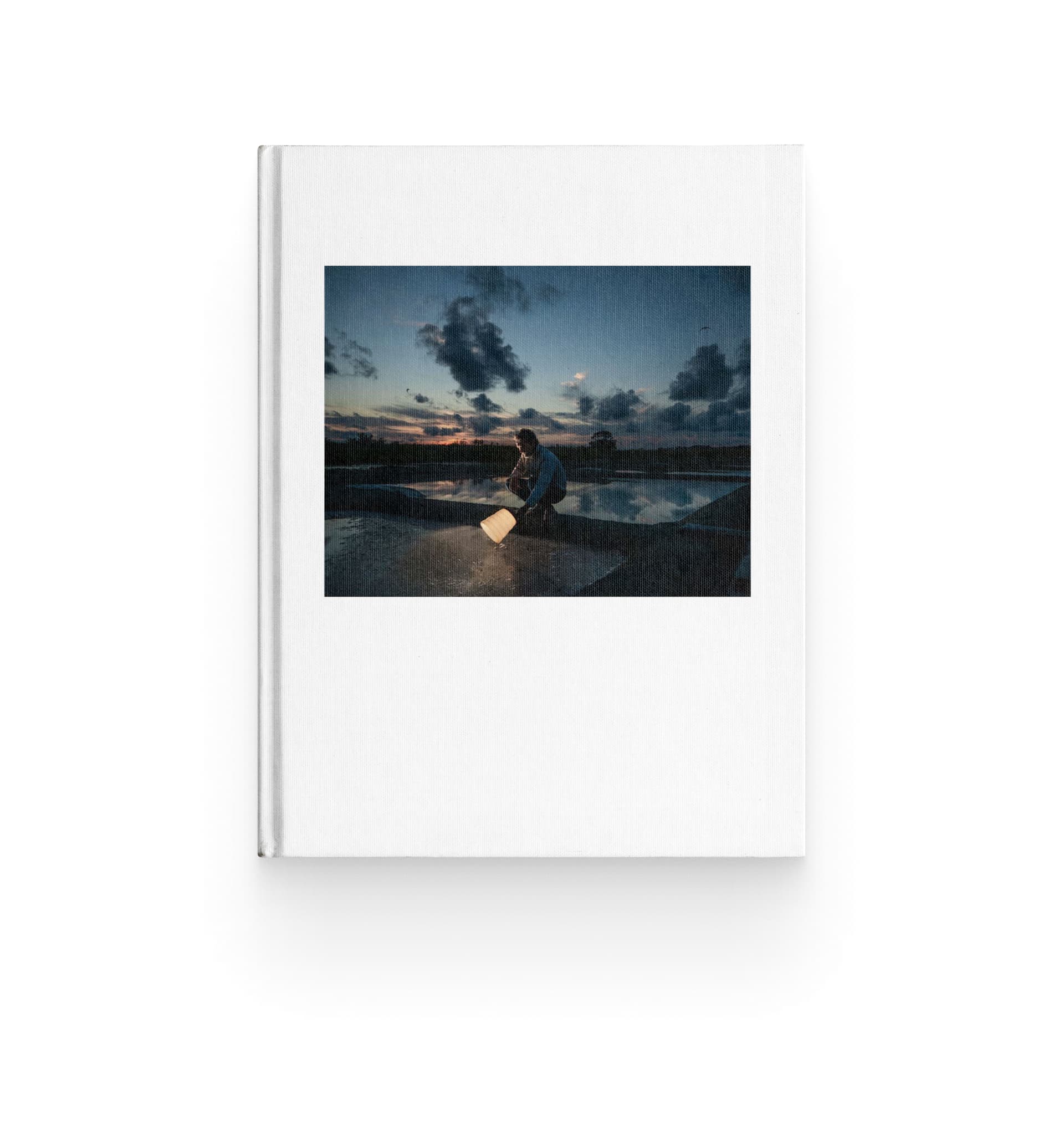

“With Tilia – which as I was saying stems from the study of mathematical and physical principles, like the Fibonacci sequence or fractal structures, in the natural environment – I have tried to create a lighting system that would obey that type of logic: lighting that is not rigid, but seems to expand into space with the same naturalness of a living organism. We will offer two different configurations, a more compact, vertical structure, and a larger, more theatrical structure, always keeping a balance between lightness and visual presence. The light emitted is soft, warm, enveloping. The diffusers in opaline frosted borosilicate glass, in fact, create an almost ethereal soft glow, like a cloud suspended in the space.”

How do you put aside the technical appeal of an object based on the rules of physics?

“I have worked on a material sensibility. Instead of being hidden, the connections become small gems, the diffusers are in frosted glass and emit a soft, enveloping light. I wanted the chandelier to be an almost spontaneous presence, as if it had always existed; but at the same time it should reveal all of its constructive complexity, when it is observed more carefully. Tilia is a project that speaks of growth and adaptability, bringing a sense of lightness, wonder and natural harmony.”

How did the concept evolve?

“Talking with Matteo Urbinati, design coordinator and marketing director of Foscarini (ed.), we discovered a shared fascination regarding natural structures and their rules of growth. From that point, I went deeper into the theme of branching, studying how to develop a new ‘botanical species’ of light, with its own logic of expansion.”

Dissonance and asymmetry are always factors in your work. Why are they important?

“We live in a world of perfect objects, while as human beings we are imperfect and diverse. An asymmetrical object can seem closer to us, more human. Not all companies will accept asymmetrical products, because they are harder to cope with at the level of production, and might be less appealing to the public. But I believe that beauty lies in this imperfection.”

Design today should get closer to people. This is constantly asserted, yet it still seems like a rare achievement…

“It’s true, design has always said this, and I think it has always tried to do it as well, but it often runs up against the needs of the market, trends and fashions, that take the objects elsewhere with respect to the wishes of designers. At times I even find myself refraining from openly stating inclusive choices: for example, I might raise a sofa by 3 cm without telling the company, knowing that this adjustment will make it easier for senior citizens to stand up. Design has to be sensitive to bodies and reality.”

You have said: “design is a solution of conflicts, and therefore it grows”. Is this an approach that can also be applied in everyday life?

“Design pushes those who practice it to reflect on things, to build on what exists in order to improve it, to try to make a positive contribution to situations, to find a dialogue between opposites. These are qualities that can truly make the difference when applied to everyday life. Not to mention the other marvellous thing about design, which is that it makes us be forever children, opening our eyes and teaching us to grasp the wonder all around us. If this isn’t the key to wellbeing, I don’t know what that key might be.”

Light that is not just function, but presence, character, and expression.